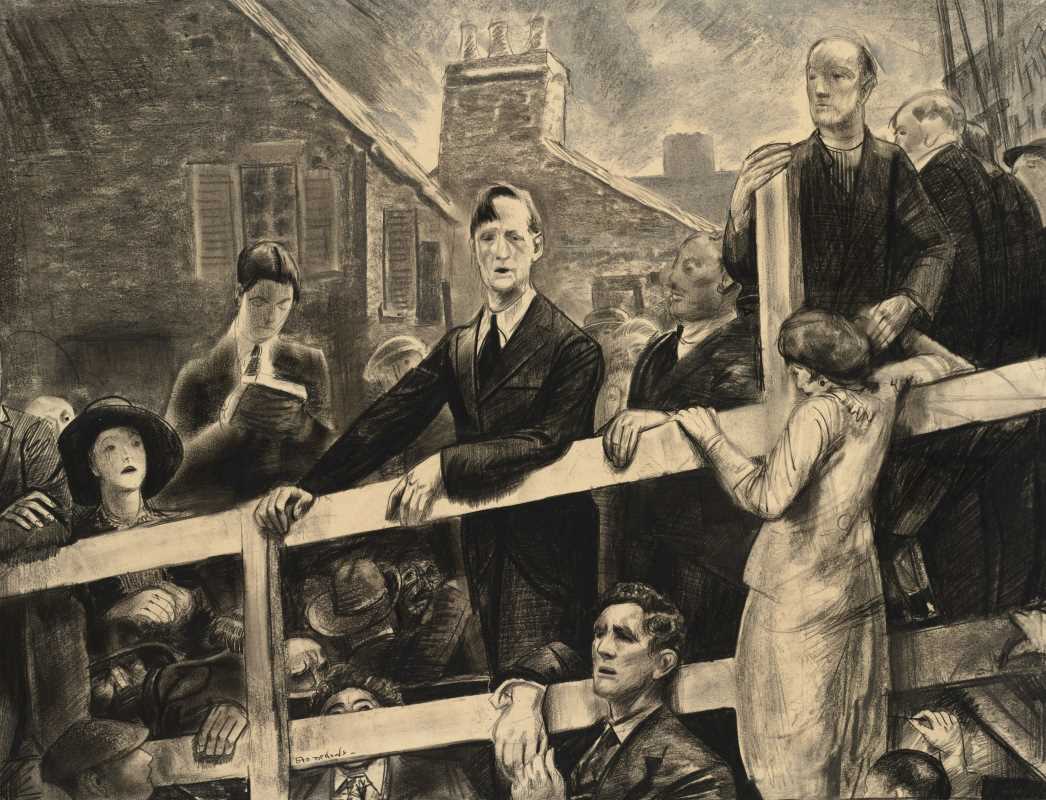

Surrealism, with its dreamlike landscapes and bizarre imagery, often appears untethered from reality at first glance. However, beneath the layers of abstraction lies a dynamic and deeply rooted blueprint of political commentary. Born out of a period of global unrest and intense ideological battles, the surrealist movement used its distinct visual language to critique authoritarian regimes, war, capitalism, and societal norms.

Despite seeming fantastical, many surrealist works remain pointedly grounded in the harsh realities of the human condition and the socio-political turbulence of the 20th century. Through their imaginative and often cryptic creations, surrealist artists spoke truth to power in ways that remain timelessly impactful.

Surrealism as a Response to Political Chaos

The surrealist movement emerged in the aftermath of World War I, a time when humanity was grappling with the devastation of war and the fragility of peace. Spearheaded by André Breton, who wrote the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, the movement was fueled by a sense of disillusionment with traditional societal structures, which many felt had failed to prevent catastrophe. The artists who formed surrealism sought to transcend conventional thinking and expose hidden truths through the unconscious mind, a realm they believed was freer from external influence.

But surrealism wasn’t just an aesthetic movement; it was inherently political. Many surrealists aligned themselves with leftist ideologies, including Marxism and anarchism, viewing art as a tool for revolution. They saw creativity not as a personal endeavor but as a collective act to disrupt oppressive norms and institutions. Their allegiance to political change permeated their works, with symbolic imagery often acting as a critique of the societal systems they opposed.

Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931) is an early example of surrealism’s pointed subtext. While it is often interpreted as a meditation on time and the unconscious, some critiques have tied its melting clocks and barren landscape to the political anxieties of a post-war generation. The disorientation of the painting mirrors the instability felt across Europe as nations rebuilt while fascism quietly seeped into political life.

Fighting Fascism Through Art

World War II and the rise of fascist regimes in Europe became pivotal in shaping surrealism’s political direction. Germany, Italy, and Spain were transforming under oppressive leadership that controlled culture and art to reinforce their ideologies. For many surrealists, their work became an act of resistance.

Joan Miró, a vocal opponent of Francoist Spain, is renowned for embedding political defiance into his art. Miró’s Aidez l’Espagne (Help Spain) (1937) is one such example, produced during the Spanish Civil War. The chaotic and fiery composition implores viewers to consider the human cost of the conflict. Through this work, Miró uses surrealist abstraction to depict the brutal suppression of the Spanish people, simultaneously raising awareness of the urgent need to support the anti-fascist cause.

Pablo Picasso’s monumental work Guernica, while not strictly surrealist, also embodies the surrealist ethos. Created in 1937 in response to the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica by Nazi and Italian forces, the piece uses fragmented forms and distorted figures to communicate the horrors of war. The surrealist influence is evident in its chaotic composition and nightmarish imagery, which evoke the disarray and terror of violence. Every figure and symbol on the canvas, from the screaming horse to the weeping mother cradling her child, is imbued with raw emotion, resonating far beyond its immediate historical context.

Through such works, surrealist artists effectively used their medium to expose the devastation wrought by authoritarianism. This crisscross of creativity and rebellion proved that art could be a weapon as powerful as any political speech.

Surrealism’s Personal Critiques of Power

Surrealism did not restrict its political messages to grand narratives of war and fascism; many works also critiqued the microcosms of power embedded in everyday life. The movement often targeted wealth inequality, colonialism, and gender oppression, shedding light on issues that were otherwise sidelined.

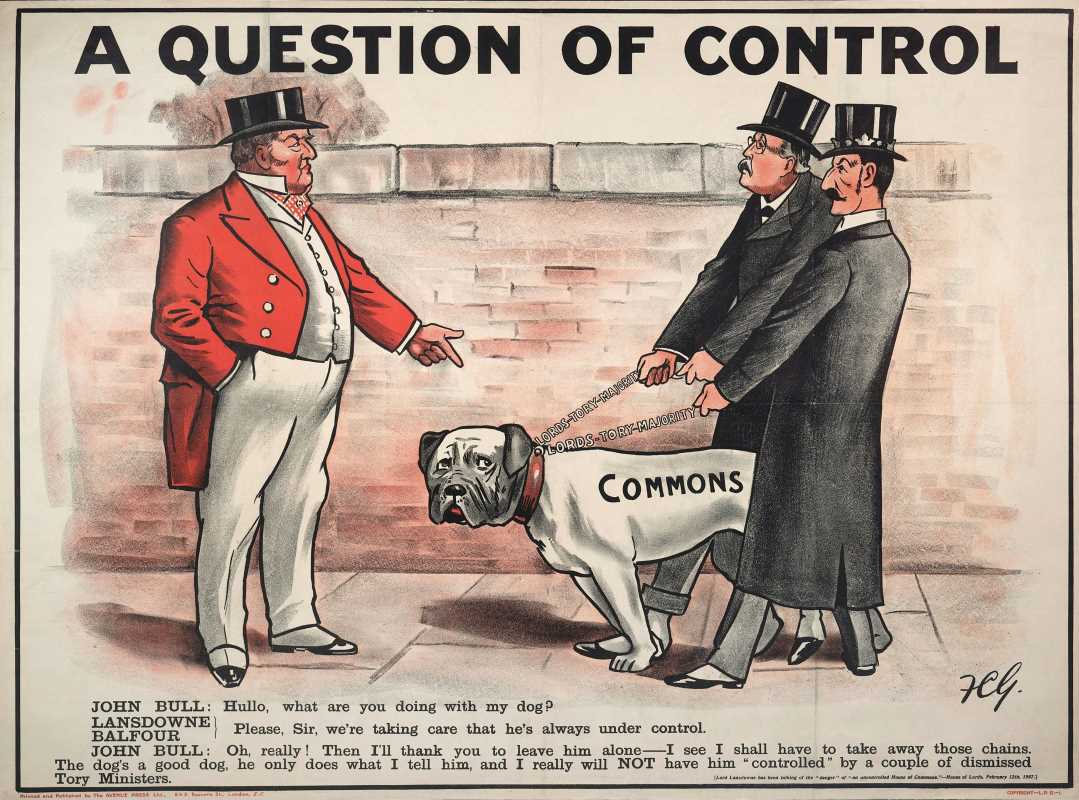

René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (1929) challenged establishment narratives with its infamous inscription, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”). While the work appears lighthearted, its commentary goes deeper. The outright denial of the image’s meaning critiques the manipulation of truth in political propaganda and capitalist advertising. Magritte’s seemingly mundane depictions often masked biting critiques of conformity and the exploitation of perception as a tool for control.

André Breton himself advocated strongly for anti-colonial movements, intertwining surrealism with the fight against imperialist exploitation. Many surrealists turned to non-European symbolism, not as means of appropriation but as an acknowledgment of the cultural heritage often suppressed under colonial rule. Surrealist exhibitions frequently featured African, Oceanic, and Indigenous art alongside European works. This integration highlighted the injustices inflicted upon colonized societies and pushed for a more inclusive conversation about creativity and global exchange.

The movement also paved the way for critiques of gender inequality through its exploration of sexuality and identity. Women surrealists like Leonora Carrington and Frida Kahlo used their unique voices to call out patriarchy and societal expectations. Carrington’s Self-Portrait (1937–38) juxtaposes wild, fantastical elements with the domesticity imposed upon women, offering a powerful reclamation of agency.

Through these personal critiques, surrealism reveals itself not just as a broad vehicle for social commentary but also as a deeply introspective exploration of power on multiple levels.

Symbols, Dreams, and Politics

Surrealist artworks are rife with recurring symbols that mask and reveal their political messages. These visual metaphors blend seamlessly with the dreamlike quality of surrealism, challenging viewers to decode hidden meanings.

For instance, Max Ernst, a key figure in surrealism, frequently used birds in his work, such as in his painting The Robing of the Bride (1940). At first glance, the fantastical avian forms suggest whimsical surrealist tropes. However, deeper exploration reveals an unsettling symbolism of predation and vulnerability, reflecting themes of surveillance, violence, and oppression during a time of escalating global conflict.

Surrealist art also often relies on juxtapositions to convey tension. Objects that are ordinary in isolation, when placed together, create unease or dissonance, encouraging viewers to question their relationships. Such strategies extend to political critique as well. Salvador Dalí’s obsession with decaying forms and disjointed landscapes captures the deterioration of societal values under oppressive regimes.

The Enduring Legacy of Surrealist Messages

Even after its peak, surrealist ideas and aesthetics continue to influence contemporary art and politics. By emphasizing the subconscious as a realm of untapped truth, surrealism has galvanized generations of creators looking to reveal the systems of power that shape lives.

Artists like Louise Bourgeois adopted surrealist motifs to explore trauma and oppression in personal and political contexts. Her series Cells, for instance, transforms mundane objects into containers of memory, suffused with political undertones of imprisonment and psychological confinement. Likewise, modern protest art frequently draws on surrealism’s power to confront political issues. Political street art, including the works of Banksy, employs surrealist absurdity to expose societal hypocrisy and injustice.

Surrealism’s endurance proves its versatility as a tool for addressing political upheaval. By blending dissidence with dreamscapes, surrealist artists uprooted the boundary between reality and imagination, suggesting that hope and resistance can flourish even in the darkest times.

Their legacy lives on, urging us to look not just with our eyes but with our minds, to peel back the layers of power that govern our worlds. As long as there are systems to subvert and truths to uncover, surrealist art will remain a bold and necessary voice in the conversation.

.jpg)