Art, in its many forms, has long served as a mirror to society’s atrocities, triumphs, and untold truths. For centuries, colonialism reshaped the world, redrawing borders and dominating cultures. It wasn’t just a political or economic phenomenon; colonialism left deep scars on the cultural and social fabric of societies across continents.

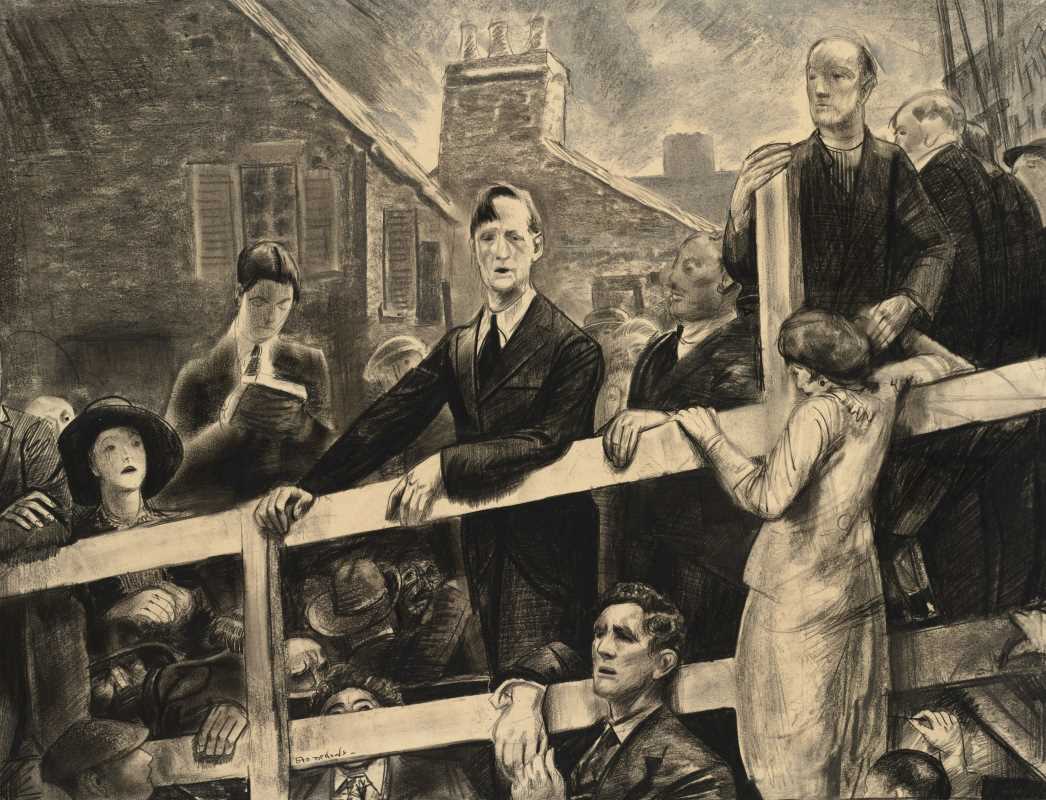

Art became a vessel for documenting these realities, not as passive decoration, but as a powerful resistance, critique, and testament to the impact of colonization. Through brushstrokes, chisels, camera lenses, and more, artists have consistently confronted, revealed, and challenged the powers that perpetuated these systems of oppression.

Documenting Colonialism as It Happened

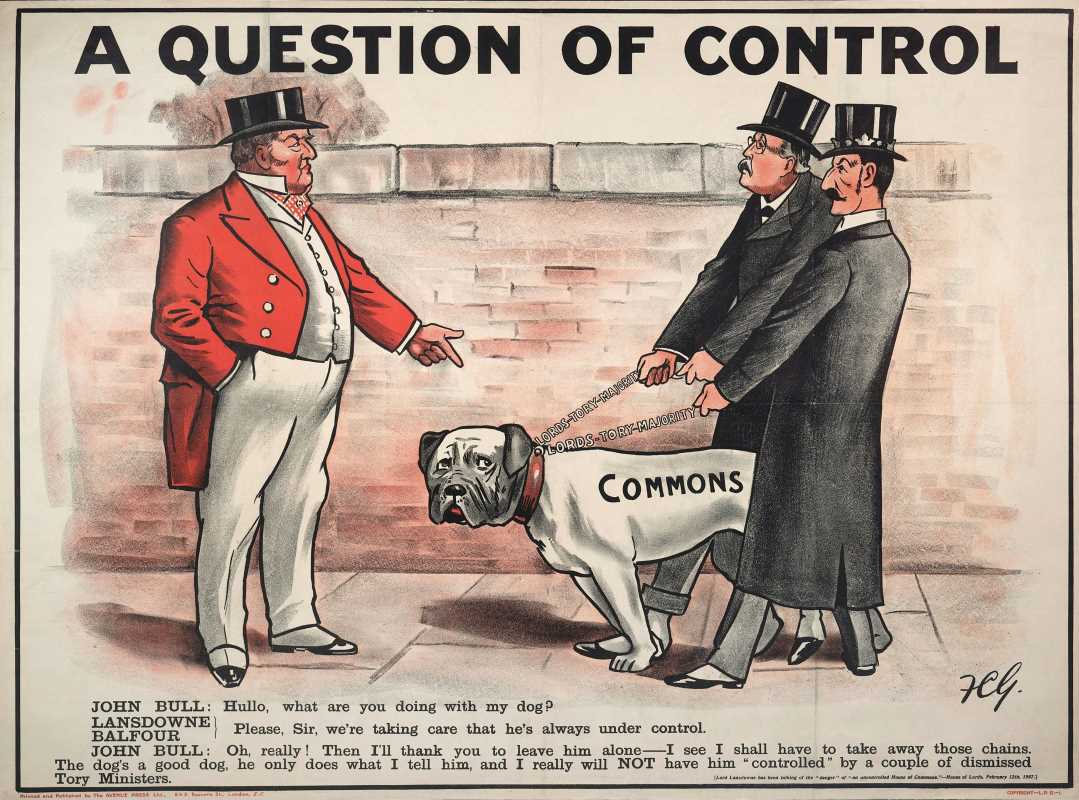

As colonial powers expanded, art became a tool to capture the narratives of conquest. During the height of the colonial era, Western art often glorified imperialism. Portraits of heroic explorers, romanticized depictions of “discovered” lands, and paintings of subjugated natives were crafted to reinforce the ideological justification for colonial expeditions. But amid this propaganda, other works and forms began acting as silent critics or alternative documentarians.

Many local artists in colonized regions turned to their crafts to preserve their cultures. For example, indigenous communities in the Americas, Africa, and Asia used traditional art forms, such as carvings, textiles, and storytelling, to record pre-colonial histories and the intrusion of foreign powers. Often, this work resisted the erasure of their identities, ensuring that their stories endured despite systemic suppression.

Japanese woodblock prints in the 19th century served as visual diaries during the arrival of Western powers under “gunboat diplomacy.” While the West romanticized Japan’s “exotic” landscapes through Orientalist art, Japanese prints, like those from the Edo and Meiji eras, reflected a complex negotiation of colonial encroachment and modernization.

Similarly, photography emerged as a critical medium, capturing the true conditions within colonized nations. Images of forced labor, famine, and poverty in places like India and Congo offered stark visual records of colonial abuses, countering the sanitized narratives presented to imperial audiences. Photography’s immediacy made it impossible, even for the most skeptical, to deny the suffering under colonial rule.

The Subversive Voices in Art

Movements of defiance through art proved that oppression could birth extraordinary creativity. Artists subjected to colonial domination began reclaiming their mediums to subvert colonial portrayals of their conditions and humanity. Instead of allowing their cultures to be appropriated and reframed, they created works that challenged Western artistic “ownership” and assumptions of superiority.

One of the most notable figures in this regard was Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Through his enormous frescoes, Rivera shifted the narrative of imperialism to glorify the working class, indigenous heritage, and revolutionary ideals. His murals, often commissioned by the state, ironically critiqued colonial exploitation and celebrated Mexico’s pre-colonial roots. His refusal to ignore the brutal history of conquest in his art was a bold statement in a world still grappling with Eurocentric histories.

Closer to Africa, anti-colonial sentiments were woven into textiles, carvings, and fine art. Nigerian artist Ben Enwonwu redefined African art by creating modernist works grounded in deep tribal symbolism. His sculpture “Anyanwu” and numerous paintings juxtaposed the resilience of African traditions against the incursions of colonial rule. Enwonwu became emblematic of the notion that art could reclaim identity while exposing the cracks in oppressive systems.

The Surrealist movement, while largely Western, also became intertwined with anti-colonial thought. Figures like André Breton and Aimé Césaire used surrealist methods to critique colonialism conceptually, blending abstraction with political commentary. Breton once proclaimed surrealism as a means of “decolonizing the imagination.” While surrealism’s relationship with colonial art is controversial for appropriating motifs of colonized cultures, its ties to figures in the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia showcased its complex role in unraveling colonial structures.

Art as a Reflection of Lost and Suppressed Traditions

Colonialism dismantled more than economies; it severed cultural lifelines. Languages were banned, traditions were vilified, and art that thrived before colonization often found itself subject to destruction or co-option by colonial administrators. Nevertheless, artists gave voice to histories and identities through their works, ensuring that these traditions remained alive, even if underground.

The Aboriginal communities in Australia witnessed the near obliteration of their ways of life under British colonial rule. Despite efforts to erase their traditions, their art became an enduring form of resistance. Dot painting, an ancient technique integral to Aboriginal culture, continued to thrive and serve as a living testament to their connection with the land, as well as a subtle rejection of colonial land claims. Today, these works are globally renowned, a powerful reclamation of cultural identity.

Likewise, the Maori people of New Zealand channeled their arts, such as intricate carvings in wood and bone, to preserve their histories and assert their presence in a landscape rewritten by colonialists. Traditional art forms like moko (facial tattooing) have re-emerged in contemporary New Zealand, demonstrating a resurgence of pride in traditions that faced suppression.

African art forms, once exhibited as “primitive curiosities” during colonial exhibitions, gradually returned to their rightful place of reverence. Sculptures, masks, and textiles serve not only as striking representations of African spirituality but also as critiques of their misrepresentation under Western control. Artworks that were stolen during colonization and displayed in European museums continue to provoke discussions around restitution and the ethics of cultural ownership.

This theme of lost heritage also appears starkly in literature and illustration. For instance, contemporary graphic novels like Joe Sacco’s Paying the Land use visual storytelling to explore the destruction brought to indigenous Canadians due to colonization’s enduring effects. Such modern works ensure the conversation about colonialism’s consequences remains relevant.

Art Movements Seeking Reconciliation

Art hasn’t just exposed the harm of colonialism but has also sought to facilitate healing and reconciliation. From powerful public memorials to modern art installations, the creative world has pushed for conversations about justice, restitution, and accountability.

For instance, post-colonial nations have embraced artistic endeavours that reclaim landscapes once associated with colonizers. South Africa, following apartheid, redefined its relationship with its past through public art installations. Works like William Kentridge’s The Head and the Load highlight the exploitation of African soldiers during colonial wars, blending performance with historical reflection.

Similarly, Indigenous communities across the Americas and Oceania use art to reshape public spaces once monopolized by colonial narratives. Mural projects, temporary installations, and even graffiti have acted as methods of asserting ownership over stolen land. The inclusion of indigenous voices in galleries, museums, and festivals marks an ongoing shift towards dismantling colonial legacies in the art world itself.

One of the most striking examples of reconciliation through art can be seen in the collaborative nature of modern exhibitions. The British Museum’s “Indigenous Australia” exhibit worked directly with Aboriginal communities to present artifacts in context. Similarly, reparative collaborations between artists in colonizing and colonized nations highlight the potential for art to foster dialogue rather than division.

Art offers the possibility of re-examining roles, understanding guilt, and beginning anew. While it cannot undo the past, it opens avenues for empathy and introspection.

Key Lessons from Art’s Dialogue with Colonialism

Through centuries, art has worked not just to expose the realities of colonialism but also to remind us of the resilience of those impacted by it. Across the globe, artists have tackled themes of oppression, identity, and heritage, ensuring that the effects of colonization are neither forgotten nor justified.

Here are crucial lessons art continues to teach us about colonialism's legacy:

- Art is both a record of beauty and a weapon against extinction. When systems attempt to erase voices, art fills the silence.

- Diverse perspectives strengthen narratives. Works crafted in resistance to colonialism showcase the need for multiplicity over monolithic histories.

- Healing requires storytelling. Art finds ways for societies to remember, process, and act on their collective past.

- Ownership and representation matter. The restitution of stolen art and inclusion of previously silenced communities open the road toward meaningful justice.

- Art as a tool to confront colonialism offers remarkable resilience. It validates the silenced, challenges the comfortable, and transforms suffering into creativity.

An Ongoing Canvas

Colonialism may officially belong to history books, but its shadows stretch into the present. Artistic expression continues to wrestle with its implications and its ongoing effects. Each brushstroke, lyric, and chisel marks the survival and strength of cultures that refused to be erased.

Artists new and old remind us that even amidst oppression’s darkest moments, creativity persists. By engaging with these works, we honor both the struggle and resilience of those who have endured. Art, in this sense, doesn’t just expose the realities of colonialism; it ensures that the fight for freedom and representation remains visible, alive, and profoundly human.

(Image via

(Image via.jpg)