Art has long served as a medium for expressing resistance and resilience, and the twentieth century offered some of the most poignant examples of this in the context of war. From world wars to oppressive regimes and ideological conflicts, artists across the globe created works that challenged the destruction wrought by war.

Anti-war art doesn’t simply critique; it seeks to remind humanity of what is at stake, illustrating the true impact of violence. These works often bring the distant realities of war closer to home, amplifying the voices of the oppressed, traumatized, and silenced.

The Age of Extremes and the Birth of Modern Anti-War Art

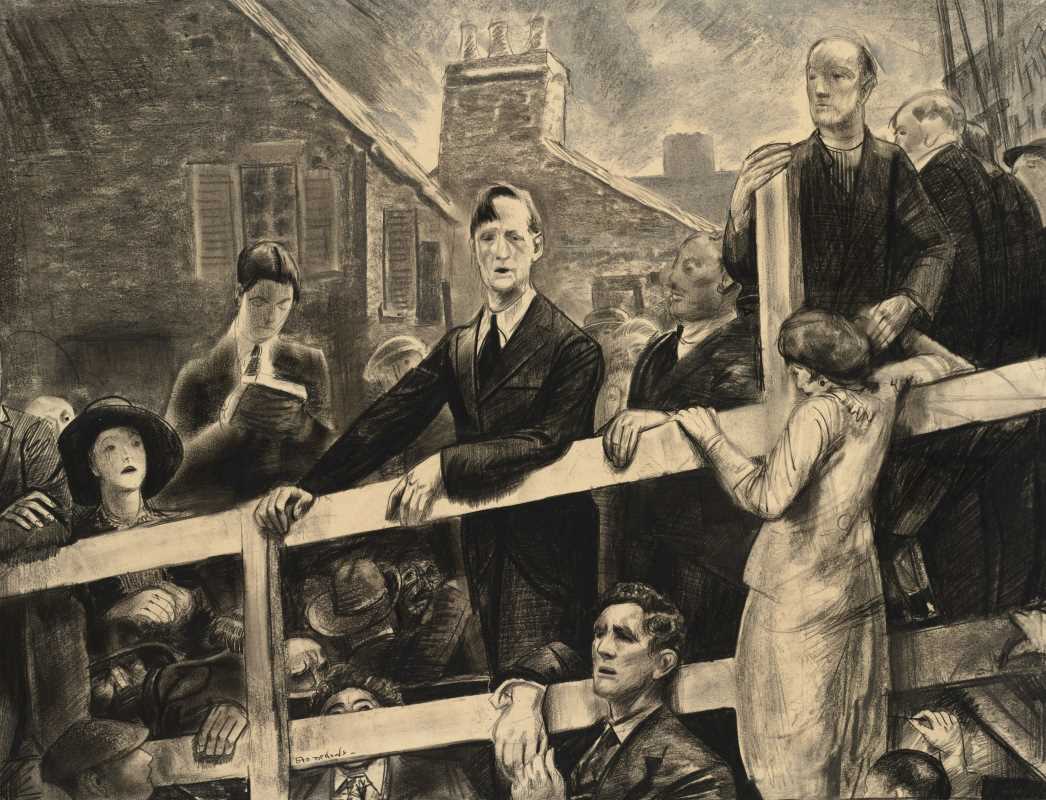

The twentieth century began with optimism but rapidly descended into chaos through conflicts such as World War I and II. These large-scale devastations prompted a new kind of artistic response, one that relied on modern techniques to portray the horrors of industrialized war. Artists no longer romanticized battle as heroic; instead, they revealed its grim truths.

After witnessing the atrocities of World War I, German expressionists played a key role in shaping early anti-war art. Otto Dix, a veteran himself, chronicled the brutalities he experienced on the front lines in his series of etchings, The War. His haunting depictions of mutilated soldiers and decimated landscapes offered a raw, uncompromising view of human suffering. Similarly, George Grosz ridiculed the political and societal forces that perpetuated war, using dark satire to highlight the corruption and complacency that fueled conflict.

The Dada movement, born partially in reaction to World War I, sought to disrupt the structures they believed led to violence. Artists like Hannah Höch and Jean Arp used collage and abstraction to convey the absurdity of war. Their rejection of traditional artistic forms mirrored a larger rejection of the systems they believed had failed humanity.

World War I’s legacy created a turning point for artists, showing that modern means of communication and creation could expose truths too often obscured by propaganda.

The Spanish Civil War and Collective Resistance

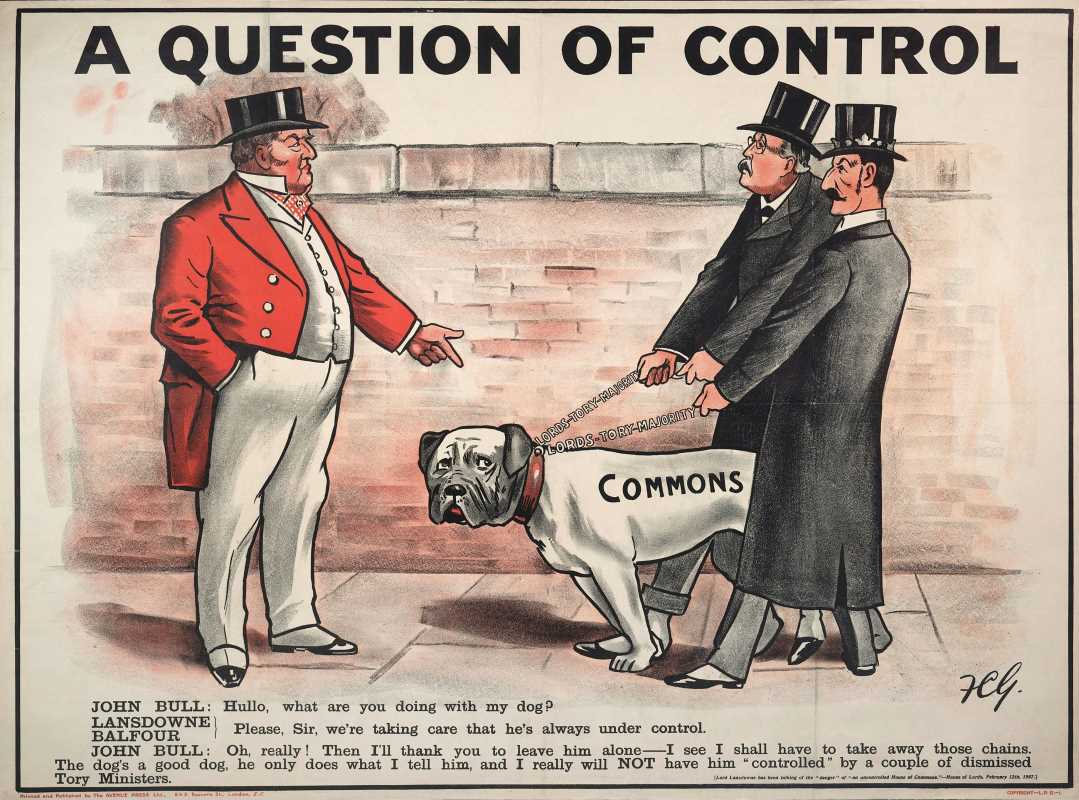

The interwar period saw the rise of conflicts such as the Spanish Civil War. This war, framed as a battle between fascism and democracy, inspired some of the most evocative anti-war art of the century. Artists used their craft not only to critique but to rally support for the anti-fascist cause.

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica stands as one of the most iconic anti-war artworks of all time. Created after the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during Spain's civil conflict, the painting’s chaotic composition and distorted figures convey the terror and anguish of innocent victims. The symbolism within the work, from the dismembered bodies to the grieving mother and child, continues to serve as a searing indictment of violence against civilians.

Joan Miró also responded to the Spanish Civil War with his piece The Reaper, where his surrealist imagery incorporated Catalan heritage with a call for resistance. Meanwhile, photographers like Robert Capa captured the conflict in real time, bringing its raw realities to international audiences. His iconic photograph, The Falling Soldier, highlighted the immediacy and fragility of life in wartime.

The collective message across these works was clear: this was not merely a national conflict, but a reflection of a global ideological divide. Art created during the Spanish Civil War bridged international solidarity, proving its role as both a witness and a weapon against tyranny.

Second World War and Its Aftermath

World War II presented horror on an even larger scale, with millions of lives lost and the Holocaust revealing the depths of human cruelty. Artists from around the world responded to this unparalleled devastation with works that united grief, anger, and a longing for accountability.

Surrealists such as Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst used their dreamlike yet disturbing imagery to comment on the chaos of war. Dalí’s painting Face of War features a skeletal face filled with endless repetitions of anguished expressions, symbolizing the cycles of death and despair caused by conflict. Ernst’s works, created during his exile from Nazi Germany, often reflected the displacement and desolation felt by so many during this period.

Meanwhile, official war artists in countries such as Britain, like Henry Moore, took to documenting civilian experiences. Moore’s drawings of figures sheltering in the London Underground during air raids humanized wartime trauma, steering away from sanitized narratives of resilience. Similarly, Käthe Kollwitz, who lost her son in World War I, created woodcuts during World War II that mourned lives lost to another senseless global catastrophe. Her Seed for the Planting Shall Not Be Ground reflected her refusal to glorify war, focusing instead on its toll on human life.

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought additional urgency to anti-war art. Japanese artists responded with images of shattered cities and scarred survivors. Panoramic devastation became a visual language that conveyed the unprecedented consequences of modern warfare to the world.

Vietnam War and the Rise of Protest

By the late twentieth century, the Vietnam War marked a critical moment for anti-war art, particularly in its connection to broader protest movements. This was a conflict where public dissent played a significant role in shaping both policy and perception, and art was at the center of this cultural wave.

Photographs and televised footage often exposed the brutality of the war. Nick Ut’s image of Phan Thi Kim Phuc, known as The Napalm Girl, shocked the international community and became a rallying cry against the Vietnam War. Similarly, artist Martha Rosler addressed the contradictions of the conflict by juxtaposing domestic scenes of opulence with war imagery in her House Beautiful series, exposing the disconnection many Americans felt about the war's reality.

Countercultural movements of the 1960s also embraced experimental art forms to convey anti-war sentiment. Musicians, poets, and visual artists used festivals, murals, and poster art as sites of collective resistance. Anti-war posters emerged as a particularly powerful medium, blending iconography like dove symbols and peace signs with bold, colorful protests against the military-industrial complex.

This period also saw abstract and conceptual artists addressing themes of war. For example, Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s performance piece Bed-In for Peace blurred the lines between activism and art, using simplicity and repetition to convey a clear anti-war message. Through these varied mediums, artists were able to challenge power structures and connect international movements for peace.

Contemporary Art and the Legacy of Peace Advocacy

War has remained a consistent reality into the twenty-first century, and contemporary artists continue their efforts to interrogate its causes and effects. Reflecting both past traditions and new approaches, their work amplifies voices that are often ignored while imagining the possibility of peace.

Ai Weiwei’s installations often address displacement caused by war. His piece Law of the Journey, featuring a massive inflatable boat filled with faceless refugee figures, focuses on the human consequences of modern conflicts that force mass migrations. Similarly, the work of Iraqi artist Wafaa Bilal incorporates technology and performance to engage audiences in interactive critiques of war and militarization.

Artists today work in an era when war is often reduced to distant news footage or overlooked altogether. Their efforts seek to counteract apathy and refocus attention on the human and environmental costs of conflict.

Through Art, A Plea for Humanity

Anti-war art during the twentieth century reveals the timeless power of creativity to critique, document, and push for change. From the trenches of World War I to the refugee crises of today, artists have consistently amplified the voices of the vulnerable while refusing to normalize violence. This legacy of resistance and advocacy reminds us not only of war’s horrors but also of the enduring hope for peace.

By showing the immediate and long-term effects of conflict, these works challenge both governments and their citizens to consider the implications of war. They remind us that peace is not just an ideal but a necessity, one that requires continued reflection and action. Art, as both a mirror and a messenger, remains a vital part of that process.

.png)

.jpg)