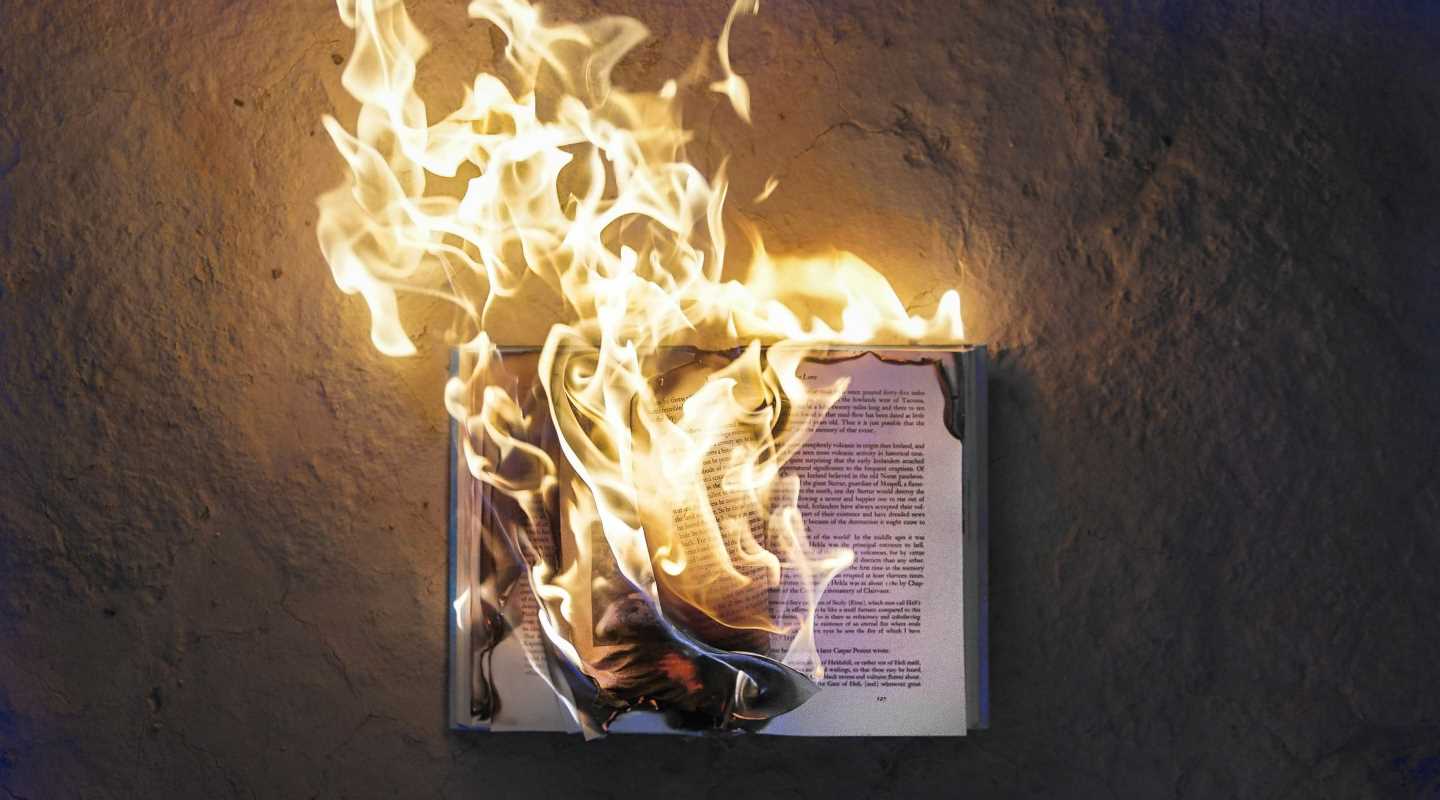

Few acts evoke as much cultural and emotional resonance as the destruction of books. Throughout human history, book burnings have served as a symbolic, and often literal, suppression of ideas, stories, and dissenting voices. Despite their violent finality, these events often transcend the physical destruction of pages and ink, leaving behind scars on cultural, intellectual, and societal landscapes. By exploring the history and motivations behind these acts, we uncover their profound consequences on freedom of expression and the preservation of collective heritage.

Tracing the Origins of Literary Destruction

Book burnings as a means of control or expression stretch back centuries, proving that written words have always been seen as both a threat and a power. Ancient societies often targeted texts seen as disruptive or nonconforming to prevailing ideologies.

One of the earliest recorded examples comes from China’s Qin Dynasty in 213 BCE, under Emperor Qin Shi Huang. Seeking to consolidate political power and eliminate dissent, he ordered the burning of texts that contradicted his policies. Scholars were also executed to further quash intellectual rebellion, a stark testament to the lengths authoritarian regimes go to control narratives.

Medieval Europe was no stranger to book burnings either, especially during periods of religious conflict. The Catholic Church often targeted texts branded as heretical, including works by early reformists like Jan Hus or Giordano Bruno. These burnings weren’t merely acts of censorship but messages intended to extinguish challenges to religious authority.

One of the most infamous cases took place in Nazi Germany in 1933. Adolf Hitler’s regime orchestrated mass burnings of books authored by Jewish writers, political dissidents, and anyone whose work didn’t align with Nazi ideology. These public spectacles were both ceremonies of cultural cleansing and warnings to those who valued intellectual resistance.

The act of burning books, though destructive, has thus often been paradoxically emblematic of the vulnerability and power inherent in literature. Those who seek to erase texts also acknowledge their enduring capacity to challenge, inspire, and influence.

The Motivations Behind Cultural Erasure

Why do people, nations, or regimes choose to destroy books? The reasons are as multifaceted as they are unsettling. At their core, book burnings stem from a desire to control narratives, eliminate dissent, or even reshape communal memory.

Ideological control forms one common motivation. Totalitarian regimes in particular use the destruction of literature as a tool to uphold unity by force. When opposing ideas are deemed unfit for public consumption, eliminating them through fire becomes a means of silencing alternative viewpoints. It’s an act of fear disguised as authority.

Religious fervor and dogma have also historically fueled these outrages. Religious leaders, for example, have burned texts considered blasphemous or heretical to protect spiritual orthodoxy. These acts are framed as purification rituals intended to preserve the faith or protect followers from moral corruption.

Sometimes, destruction is less about rebellion and more about symbolism. Victor Hugo’s Notre Dame de Paris describes how manuscripts were occasionally burned by illiterate zealots who feared what they didn’t understand. Similarly, extremists may burn books without having read them, viewing knowledge itself as an existential threat.

Finally, cultural or ethnic suppression lies at the heart of some book burnings. When conquerors or colonial powers seek to dominate a region, they often aim to erase the stories, languages, and histories of the people they subjugate. The obliteration of libraries, scripts, or oral traditions amounts to a systematic attempt to rob communities of identity and legacy.

The motivations may differ, but the outcome is disturbingly similar: the deliberate impoverishment of a society’s intellectual and cultural domains.

The Enduring Consequences of Burning Books

The physical destruction of literary art may seem finite, but its ripples leave profound, long-term effects on the societies affected. The loss of knowledge, erosion of intellectual diversity, and chilling effect on free expression are just a few of the dire consequences.

One of the most immediate impacts is the loss of information. When texts are destroyed, the knowledge they hold can disappear entirely. The burning of the Great Library of Alexandria is a poignant example of this. Though accounts of who or what caused the fire may vary, the loss of countless ancient texts and accumulated wisdom left a permanent void in the intellectual progress of its time.

Book burnings also contribute to the narrowing of perspectives. Destroying works that present alternative viewpoints limits access to ideas that could inspire innovation or personal growth. The chilling effect on dissenting voices is palpable; writers, thinkers, and educators may self-censor out of fear, leading to decades, or even centuries, of intellectual stagnation.

Another long-term consequence is the erasure of cultural memory. Whether it’s the destruction of language during colonization or the obliteration of stories during genocides, targeting books cuts threads that tether communities to their heritage. Burning indigenous texts, for instance, was a common tactic of European colonizers, leaving many native populations disconnected from their ancestral knowledge and traditions.

Book burnings also fray the fabric of a global literary community. Each destroyed text represents a piece of shared humanity lost to the flames. Collective empathy and reliance on past wisdom diminish when we allow cultural artifacts to be destroyed.

Paradoxically, however, history often shows that suppressed works gain visibility after such acts. The act of burning books can cement their importance, transforming them into enduring symbols of resistance. The works of writers like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Anne Frank, or Salman Rushdie, targeted for censorship or destruction, have become icons of freedom of expression.

Lessons on Free Expression

At their core, book burnings reveal the fragility and resilience of free expression. By targeting literature, regimes and movements underline the profound connection between the written word and human liberty. Literature acts as the voice of identity, critique, hope, and imagination. Destroying it signals deeper societal cracks.

Yet, books endure because free expression cannot be entirely eradicated. Underground movements are living proof of this. During the Soviet era, banned literature known as Samizdat circulated covertly, allowing people to engage with truths denied to them. Even in digital spaces, blacklisted books find new homes online, transcending borders and firewalls.

Engaging with such histories reinforces the importance of defending not only books but also freedom of thought and debate. Advocacy for literacy campaigns, intellectual inclusion, and the safeguarding of libraries ensures that we remain vigilant against forces that wish to suppress knowledge.

A commitment to free expression involves more than written laws; it thrives in an open, informed cultural mindset. Teaching youth about the power of books encourages them to value their significance, making repression harder to normalize. After all, as Heinrich Heine once warned, “Where they burn books, they will also, in the end, burn people.”

Preserving Cultural and Literary Heritage

With the evolution of societies, the preservation of literary art has grown from parchment and print to digitized archives and international safeguards. Nonetheless, the responsibility of protecting works doesn’t solely rest on institutions; it begins with individuals.

Here are some forward-looking ways we can act to preserve literature and culture:

- Encourage public engagement with diverse books through book clubs and storytelling events

- Support libraries, especially those in marginalized communities, to ensure equitable access to knowledge

- Advocate for international treaties that protect both literature and cultural artifacts held in conflict zones (e.g., the Hague Convention)

- Teach media literacy, helping people discern the value of diverse perspectives and narratives

- Utilize technology for archiving at-risk texts, ensuring they survive the passing tides of history

By continuing to celebrate the beauty and importance of books, we honor their role as guardians of culture, ideas, and collective identity. Literature reflects both our imperfections and aspirations, making its protection crucial not just for the present but for the future.

Book burnings may cast oppressive shadows, but like phoenixes from ashes, the stories they try to silence often emerge stronger. Through safeguarding our literary heritage and championing freedom of expression, we shape communities where books are eternally valued, their words echoing long past the flames.

.jpg)