Art possesses the unique ability to challenge authority, question societal norms, and give voice to dissent. During the rise of fascist regimes in the 20th century, artists around the world employed their creativity to resist oppression, expose injustice, and inspire hope.

Whether through visual art, music, or theater, these acts of resistance became as much a part of history as the regimes they opposed. Here are five significant examples that highlight the profound impact of artistic opposition to fascism.

Dadaism Against Naz*sm

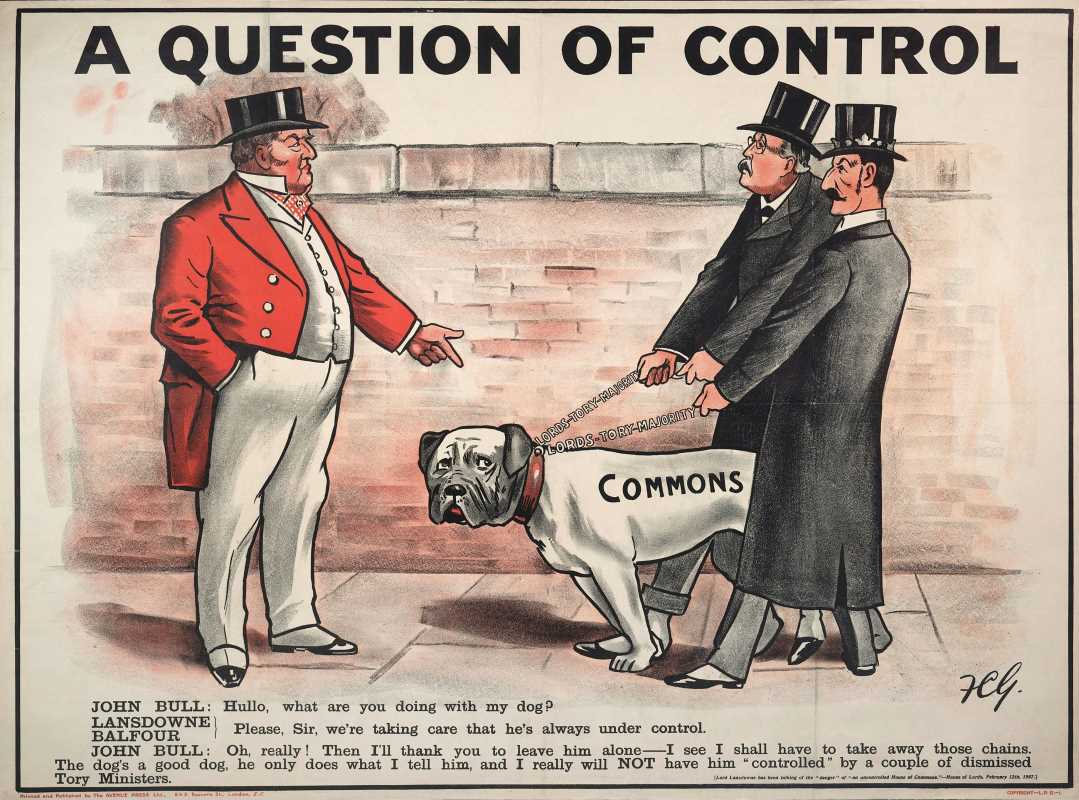

The Dada movement, born in the aftermath of World War I, famously rejected traditional art and societal norms. While its roots predated Hitler’s rise, Dadaism evolved into a weapon of defiance against the oppressive ideologies of Nazism. Artists like Hannah Höch, John Heartfield, and George Grosz used their nonconformist spirit to critique authoritarianism, militarism, and xenophobia.

John Heartfield, in particular, turned photomontage into a political art form. His piece The Meaning of the Hitler Salute (1932) exposed the interplay between corporate greed and the Nazi regime, showing a wealthy industrialist placing money into Hitler’s palm. Grotesque yet poignant, his works dismantled fascist propaganda with wit and bold satire.

Hannah Höch used photomontage to critique the subordinate role of women in fascist ideology, layering fragmented images that symbolized societal dissonance. Meanwhile, George Grosz created paintings and drawings portraying the chaos and moral decay within Nazi leadership.

By mocking fascist ideals, Dadaists wielded absurdity to expose the inherent absurdity of authoritarian control. Though many of these artists were forced to flee or go underground, their work laid the groundwork for a legacy of fearless artistic activism.

Anti-Fascist Murals in Spain

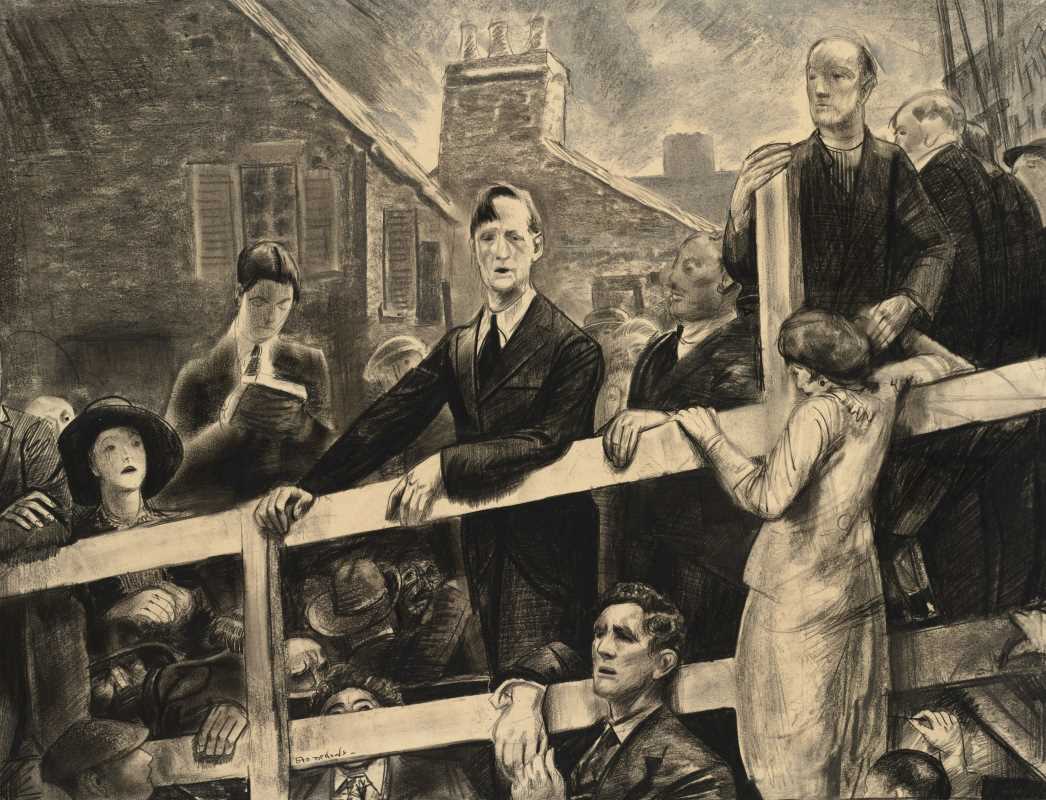

The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) saw artists rising against Franco’s fascist forces with monumental murals that painted stories of resistance, solidarity, and suffering. These large-scale works not only adorned public spaces but also became physical embodiments of the anti-fascist movement.

One of the most iconic artists of this era, Pablo Picasso, created Guernica (1937) in response to the bombing of the Basque town of the same name. While not a mural in the traditional sense, the painting’s scale and raw emotional power gave it the weight of a revolutionary monument. Picasso’s stark depiction of brutalized civilians and fragmented forms became a global symbol of anti-fascist rage, traveling internationally to raise awareness of Franco’s violent repression.

Meanwhile, artists in Spain like Josep Renau and David Alfaro Siqueiros actively engaged in mural-making to bring anti-fascist messages to life. These murals often depicted the struggles of workers, the unity of diverse social groups, and the futility of war. Renau, who was also a prominent graphic designer, used his skills in propaganda posters and public art to rally support for the Republican cause.

Though many of these works were destroyed by the fascist regime, their spirit lived on as testaments to the courage and creativity of those who dared to speak against tyranny.

Underground Art in Mussolini’s Italy

During Benito Mussolini’s authoritarian rule in Italy, art became a battleground between state-sponsored propaganda and clandestine creativity. Mussolini sought to associate his regime with Roman grandeur, commissioning imposing statues, fascist-inspired futurism, and exaggerated depictions of the cult of personality. But in the shadows, underground artists worked to undermine his vision.

Carlo Levi, a writer, painter, and anti-fascist activist, used his art and words to challenge the regime’s narratives. His painting Lucania 61, though created after Mussolini’s fall, reflected the struggles of rural Italians during fascism. His novel Christ Stopped at Eboli stemmed from his time in political exile, exposing the poverty and neglect in southern Italy under the regime.

Even the Futurists, who were initially aligned with fascism, saw a schism in their ranks when some artists rejected Mussolini’s militarism. Umberto Boccioni and others reimagined Futurism not as a tool for empire-building but as a voice for societal freedom and modernity.

Underground resistance groups also circulated satirical cartoons, prints, and graffiti exposing the regime’s corruption and authoritarianism. Though largely anonymous and fleeting, these works sparked defiance and served as quiet acts of rebellion under oppressive rule.

Music and Theater as Resistance Tools

While visual art was often the primary medium of resistance, music and theater also emerged as powerful tools for galvanizing defiance against fascist regimes. Plays, songs, and performances offered accessible and immediate ways to unite communities and spread dissenting messages.

Bertolt Brecht, a German playwright, epitomized resistance through theater. His works, including The Threepenny Opera and Mother Courage and Her Children, critiqued authoritarianism and the dehumanizing effects of war. Brecht developed the “alienation effect,” an approach that encouraged audiences to critically engage with social injustices rather than passively empathizing with characters. Brecht’s collaboration with composer Kurt Weill led to sharp, satirical songs like “Mack the Knife,” which criticized both the bourgeoisie and the rise of authoritarianism.

Across fascist Europe, folk music also became a vehicle of resistance. Protest songs carried subversive messages that rallied the oppressed. For example, in Francoist Spain, flamenco became intertwined with outlawed political protests. Similar movements emerged in Italy, where songs in regional dialects subtly challenged Mussolini’s attempts at a uniform national culture.

Music and theater bypassed literacy barriers, ensuring that the spirit of resistance reached even the most marginalized communities. These art forms gave people a platform to question authority, share their stories, and persevere against tyranny.

The Role of Exiled Artists

For many artists under fascist regimes, exile offered not only an escape from oppression but also a new platform to challenge authoritarianism. Forced out of their homelands, these creators used their work to shed light on the horrors of fascism and inspire solidarity beyond borders.

One of the most notable exiled artists was German playwright and poet Else Lasker-Schüler, whose expressionist poetry mourned the destruction wrought by the Nazis. Max Ernst, a pioneering surrealist painter, fled Germany and became a vocal critic of totalitarianism from abroad. His works, like Europe After the Rain II, evoked haunting dreamscapes that mirrored the psychological and physical destruction of war.

Marc Chagall, a Jewish artist who fled Vichy France, created works reflecting both the joy of Jewish traditions and the tragic dislocation of exile. His paintings became vivid testaments to resilience in the face of horror.

Artists in exile often collaborated to keep resistance movements alive. Organizations like the Free German Artists and Writers group in London and the American Guild for German Cultural Freedom ensured that the fight against fascism remained visible despite geographic displacement. Their efforts amplified the voices silenced at home and created a global network of resistance through art.

Creativity as Defiance

Artistic resistance against fascist regimes proved that creativity could not be contained, even in the darkest times. From the irreverence of Dadaism to the emotional power of murals, clandestine artworks, and revolutionary music, these efforts reminded the world that dictatorship could not suppress the human spirit.

Each act of creative defiance, whether loud or subtle, served as a reminder of the resilience of those who dared to fight oppression with brushes, pens, and melodies. These artists demonstrated that resistance doesn’t just live in marches or speeches; it thrives in creativity, protest, and the shared determination to imagine a better world.

.jpg)