Throughout history, political exile has forced countless artists to leave their homelands, often separating them from familiarity and community. Yet, from this displacement has emerged profound creativity.

Stripped of comfort but filled with a need for expression, exiled artists have turned hardship into inspiration, giving birth to significant movements, styles, and iconic works. Through five examples, we’ll explore how political exile has shaped some of the most compelling art in human history.

Pablo Neruda’s Poetry of Resistance

Pablo Neruda, the Chilean poet, diplomat, and Nobel laureate, stands as one of the most well-known literary voices born from political exile. His career was deeply entangled with political activism, supporting progressive movements and voicing opposition to oppression in Chile. When a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet ousted President Salvador Allende in 1973, Neruda's life was upturned. Though he fell ill shortly after the coup and died that same year, earlier periods of exile greatly contributed to his body of work.

During his earlier exiles across Europe and Latin America due to his role in politics, Neruda’s poetry evolved into a powerful vehicle for resistance and hope. Works like Canto General, an epic that fuses the histories, struggles, and landscapes of Latin America, were fueled by his longing for justice and his displacement from his homeland. His verses spoke to the shared struggles of humanity, becoming a beacon for other artists living under suppression and exile.

Neruda’s poetry reminds us that even in displacement, art has the power to forge connections between people, places, and ideas.

Marc Chagall And the Colors of Displacement

For Marc Chagall, exile became a recurring theme, coloring his works both literally and metaphorically. Born in modern-day Belarus, Chagall’s vibrant paintings reflect his Jewish heritage, his early life in Vitebsk, and his enduring search for identity amid chaos. His first period of exile came during the rise of Bolshevism in Russia. While Chagall initially supported the Russian Revolution, the increasingly authoritarian regime made it impossible for him to continue his artistic expression on his terms.

Later, Hitler’s ascent to power in Germany made Europe even more perilous for Jewish artists. Chagall fled Nazi-occupied France for the United States in 1941, alongside many other artists escaping persecution. His time in America was both a blessing and a burden. While he was safe, he was painfully disconnected from the cultural roots that defined his work. This tension often emerged on his canvases. For instance, his painting The White Crucifixion portrays a Jewish Christ figure surrounded by scenes of European Jewish suffering, blending personal displacement with collective trauma.

Despite his exile, Chagall never lost the magical, dreamlike quality of his art. Instead, he infused it with the sorrow and yearning that came from being torn from his homeland and heritage.

Bertolt Brecht And the Theater of Exile

The German playwright Bertolt Brecht revolutionized modern theater, often drawing from his time in exile to craft stories about resistance, tyranny, and survival. Forced to flee Germany in 1933 after the Nazi regime labeled his works subversive, Brecht embarked on a restless period of exile. He lived in various countries, including Denmark, Sweden, and the United States, before finally settling in East Berlin post-World War II.

Brecht’s experiences in exile significantly shaped the development of his pioneer epic theater and his influential theory of the "alienation effect," which aimed to prevent audiences from becoming too emotionally attached to the characters so they could focus on the societal issues presented in his plays. Works like Mother Courage and Her Children and The Caucasian Chalk Circle emerged from Brecht’s fascination with human resilience during times of war and political turmoil.

For Brecht, exile sharpened his critique of authoritarianism, capitalism, and human suffering. Rather than silencing him, the forced distance from his homeland strengthened his resolve to use art as a tool for revolution and education.

Frida Kahlo’s Political and Emotional Exile

Frida Kahlo might not have faced exile in the traditional sense of displacement from her homeland, but her art reflects an internal exile born from political, physical, and emotional turmoil. A staunch communist and passionate advocate for social justice, Kahlo found herself at odds with Mexico’s political climate at times, but she also faced a more personal kind of isolation. Her marriage to Diego Rivera, peppered with betrayals and reconciliations, coupled with her numerous health struggles, created a life where exile took on a symbolic form.

One of the most pronounced instances of physical and emotional exile in her life was her trip to the United States. During her time there, she felt profoundly disconnected from her Mexican roots and critical of American capitalism. Works like My Dress Hangs There and Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States encapsulate the tension between her identity and her surroundings. The rich symbolism in her art, from indigenous culture to themes of pain and rebirth, often highlights the disorientation and longing that came with her personal and political struggles.

Kahlo’s unique approach reveals that exile need not always be geographical; it can be rooted in a sense of alienation from one’s values, heritage, or even one’s own body.

Mahmoud Darwish And The Poetics Of Palestinian Exile

Mahmoud Darwish, often called the "poet of Palestine," beautifully captured the struggles of displacement and statelessness in his poetry. Born in 1941 in a village that would become part of Israel, Darwish grew up experiencing firsthand what it meant to live in exile. Forced to flee during the Nakba (the Palestinian exodus in 1948), he grew up in various parts of the Middle East and later spent much of his life living in exile in cities like Cairo, Beirut, and Paris.

Darwish’s poetry, including works like Identity Card and A Lover from Palestine, centers on themes of identity, homeland, and longing. His words captured not only the sorrow of exile but also the strength and resilience of a people determined to hold on to their culture and heritage. For Palestinians, Darwish wasn’t just a poet; he was a voice for an entire displaced population.

His exile allowed him to see both his homeland and the broader Arab world from unique vantage points, enriching his poetry with layers of perspective and depth. Darwish’s writings remind us that art born of exile can serve as both a catharsis and an act of resistance.

Art That Transcends Borders

The stories of these artists and movements demonstrate that while exile can strip individuals of their homeland, it cannot silence their creativity. If anything, it magnifies their voices, infusing their work with authenticity, passion, and resilience that resonates across boundaries and eras. Whether painting from foreign shores or penning poems while dreaming of home, exiled artists have turned displacement into enduring masterpieces that reflect the complexity of human experience.

Art born of political exile reminds us that creation often stems from struggle and longing. The songs, paintings, theater, and poetry formed in these moments of isolation aren’t just products of adversity. They’re testaments to the unbreakable spirit of humanity, a beacon to those who may find themselves navigating the rough seas of displacement.

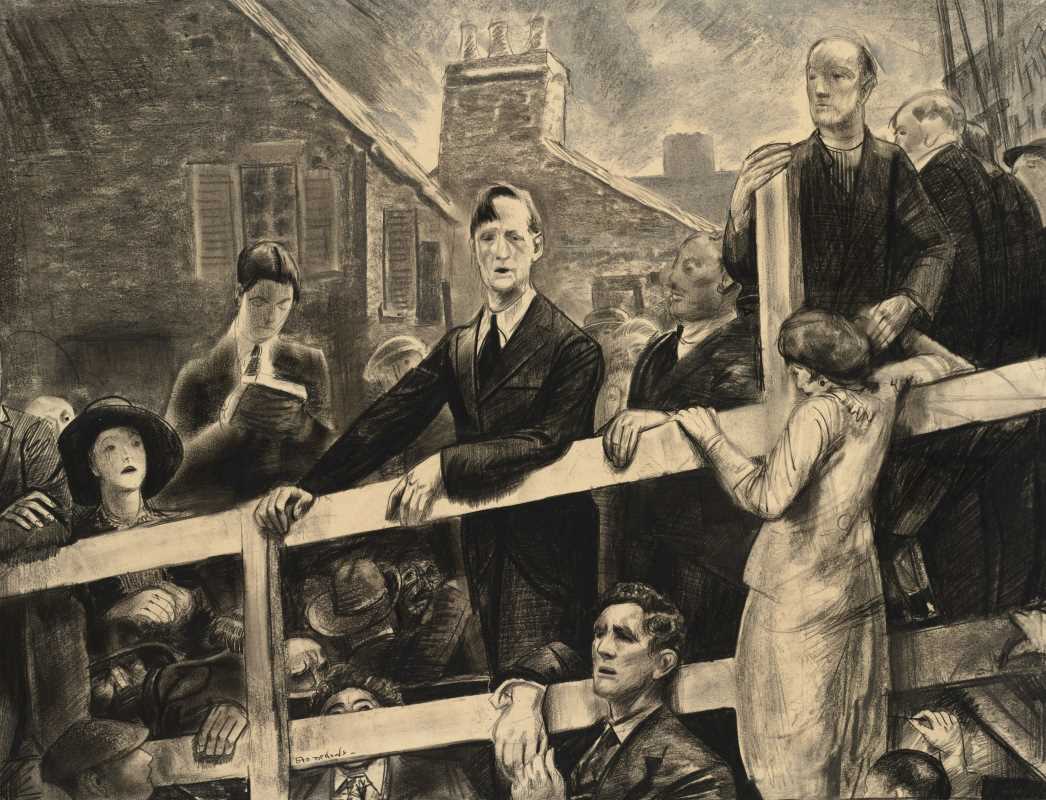

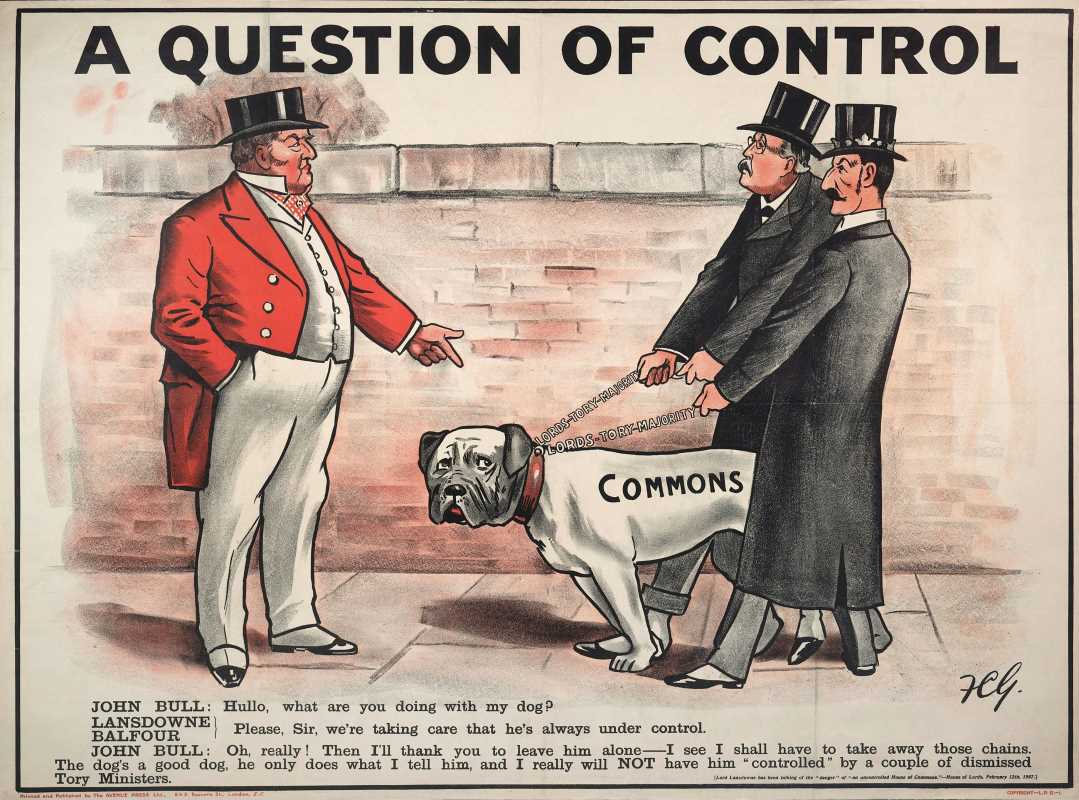

(Image via

(Image via.jpg)